Confused about Stack and Heap?

Confession, I’ve always had a hard time keeping stack and heap apart. Yes, I’ve read about memorymanagement and then memorized that objects allocated with new go on the heap. But I had to briefly think about whether the location is stack or heap. Kind of like I have to think about East and West. But what does allocate on the heap mean? Why is it different from the stack? And why does it even matter?

In Java or C#, value types (primitives) are stored on the stack, reference types on the heap. Memory allocation in terms of stack and heap is not specified in the C++ standard. Instead, the standard distinguishes automatic and dynamic storage duration. Local variables have automatic storage duration and compilers store them on the stack. Objects with dynamic memory allocation (created with new) are stored on the free store, conventionally referred to as the heap. In languages that are not garbage-collected, objects on the heap lead to memory leaks if they are not freed.

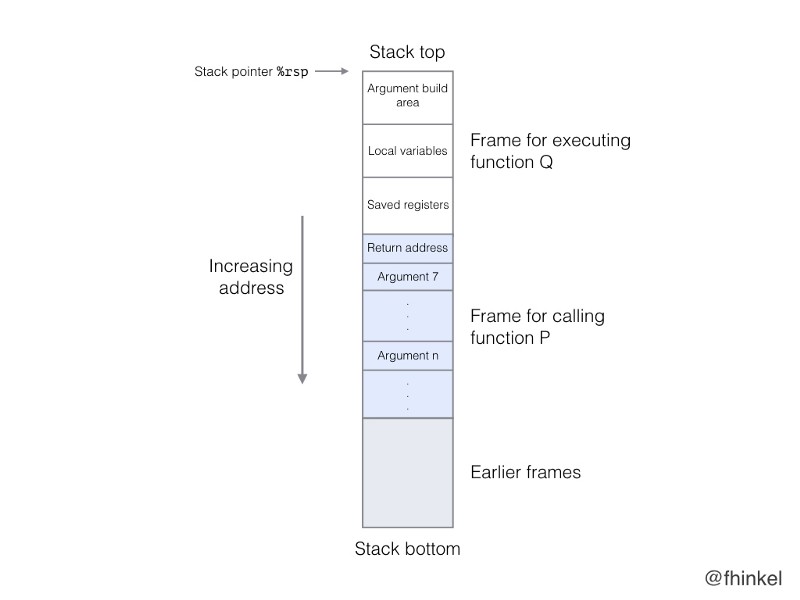

When can we allocate objects on the stack? One important detail is that the stack for storing objects is the same as the run-time call stack. The run-time stack, consisting of stack frames, is responsible for program execution and function calls. A stack frame contains all the data for one function call: its parameters, the return address, and its local variables. Stack-allocated objects are part of these local variables. The return address determines which code is executed after the function returns.

The stack frame only exists during the execution time of a function, and so do the objects on the stackframe. That has the advantage that we do not need to worry about memory leaks caused by stack-allocated objects— but the objects are also not available anymore once we return from the function.

Only objects of fixed size known at compile time can be allocated on the stack*. This way weknow the size of a stack frame at compile time, and can access objects on the stack with fixed offsets relative to the stack pointer.

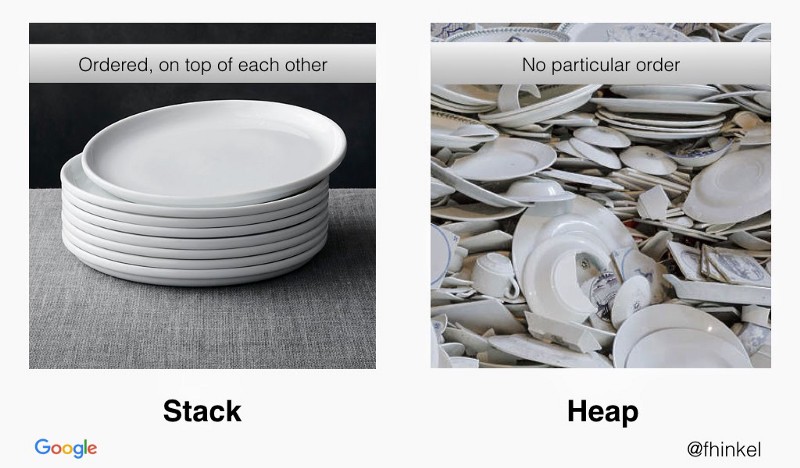

When can we allocate objects on the heap? You can think of the heap as extra storage completely independent of the run-time stack. It’s memory with no particular layout. Independent of program execution, we can ask for memory in this heap. When we allocate memory, the system makes sure that nothing else can use that same memory and invalidate our data. Objects on the heap live on after we exit the function that allocated the memory. This is good — but now it’s our responsibility to free memory on the heap, or we end up with memory leaks. In garbage-collected languages, the garbage collector frees memory on the heap and prevents memory leaks.

Stack and heap in the context of memory management have always been nebulousconcepts to me. Understanding the run-time stack finally made it click.

Stack and heap became clear to me when I read Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective (3rd Edition). Now it seems kind of obvious, but once you understand something it’s always obvious.

The book has several chapters on machine-level representation of programs. These chapters are about assembly code. One has a subsection The Run-Time Stack.

That section explains how passing control between functions affects the run-time stack. It details where parameters and return values are stored so they’re available in the called or calling function. Allocating and deallocating memory is simply decrementing and incrementing the stack pointer by an appropriate amount. If you’re interested and want to know more, the book is really helpful.

(*) Only objects of fixed size known at compile time can be allocated on the stack. Except for funny things like Variable-Length Arrays in C99. GCC allocates them on the stack.